Brewing process

At Kinn we have not striven for the very latest and most modern brewery equipment, but rather we have proudly stuck to our own designs, fabricated from pre-used stainless steel tanks. This small-scale approach is just part of the special culture that gives Kinn beers such exceptional flavour.

Crushing the malt

Brewing starts with the crushing of the malt in the grain mill. Malt is grains of barley, wheat or rye that have been allowed to sprout and dry, which is the starting point for beer. The origin of the malt is extremely important for the colour and taste of the finished product. Malt that is roasted to dry will impart a dark colour to the beer. Our favourites are coarsely ground Maris Otter from England for our Anglo-inspired beers, and Pilsner malt for our Belgian brews.

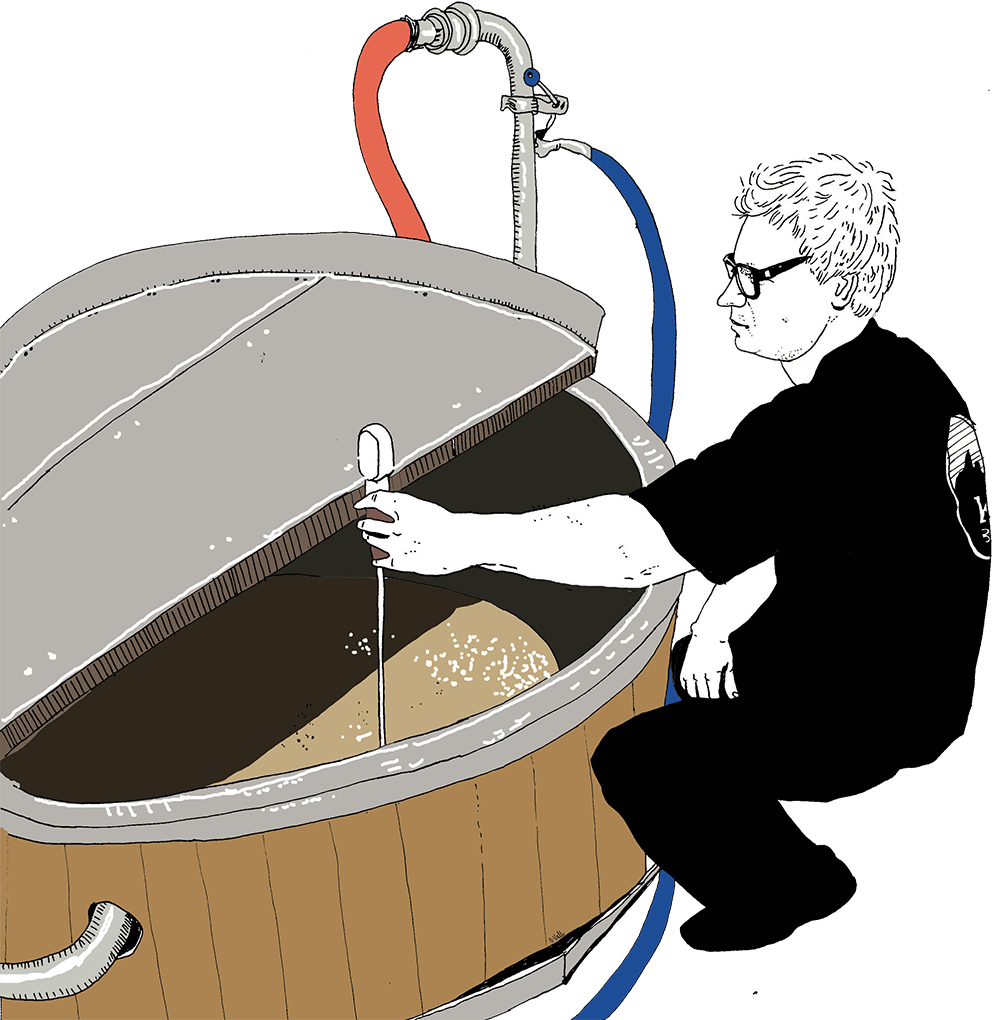

Promoting enzyme action

Once crushed and softened in hot water in the mash tun, we must carefully control the temperature. If we miss the target by more than one degree Celsius, the beer will be too sweet or too thin, as the various enzymes converting starch to sugar in the malt thrive at different temperatures. Most beers are mashed at 66 oC, although some varieties demand anything from 62 to 68 oC.

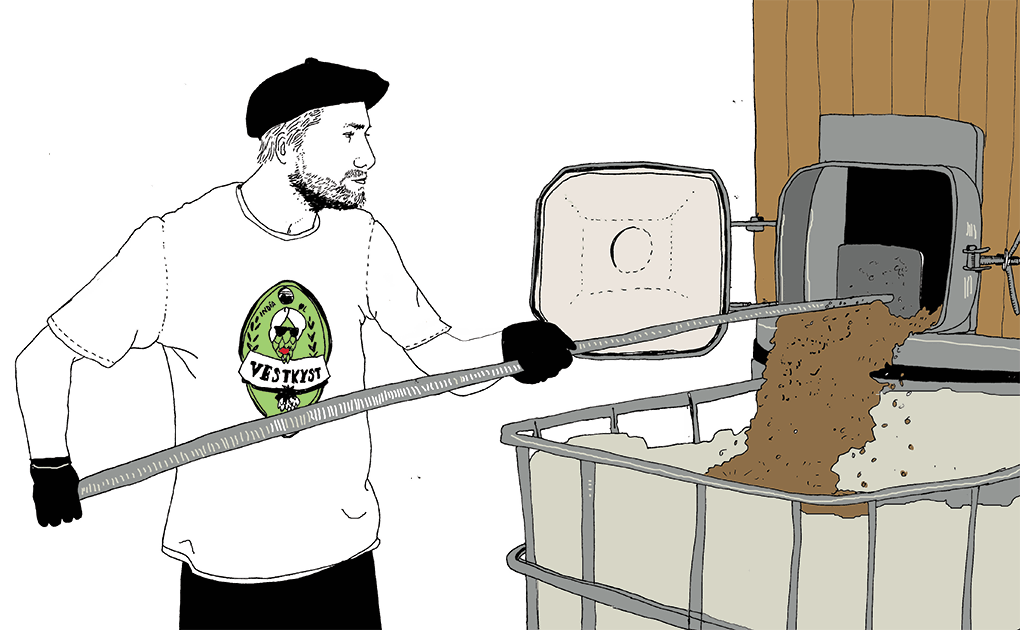

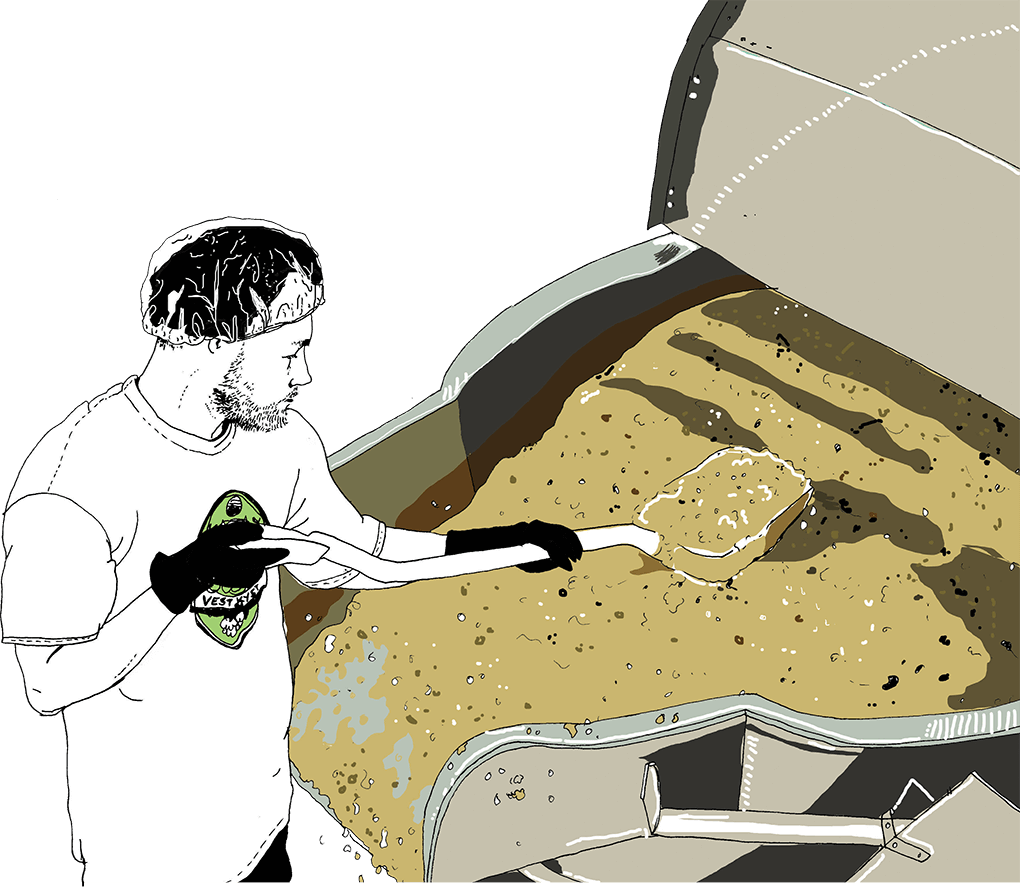

Discarding the mash

Once the early conversion to sugar has finished and the sweet wort has been pumped into the wort kettle, the mash can be discarded. This spent malt is now collected and donated to local farmers to feed their cattle and pigs. Not only does this allow us to discard our waste, but it also becomes a useful resource. A smaller quantity goes to the local bakery, to be added to a particularly delicious, local wholemeal loaf that goes by the name of Kinn Bread.

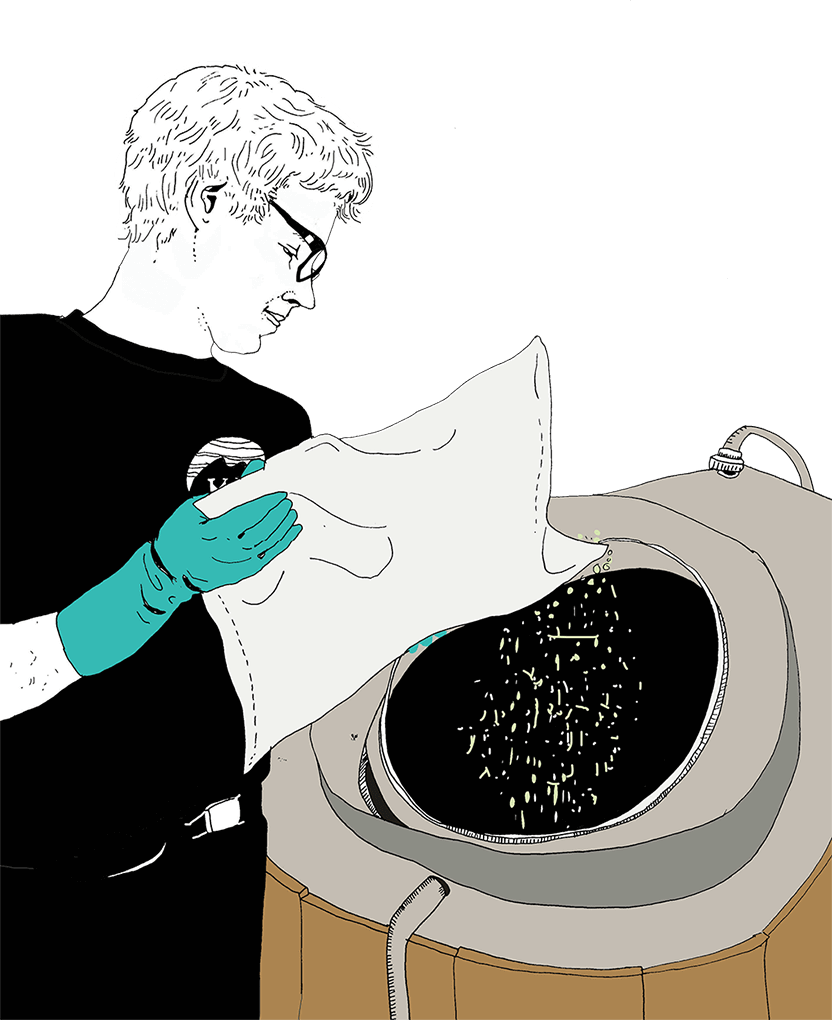

Boiling the wort and adding hops

The sweet wort needs to be boiled for sterilisation, and to drive off some of the water. During the boil, tasty hops are added. Hops are the flowers of a climbing plant that has been cultivated for almost a thousand years to add flavour to beer. The hops added at the onset of the boil provide the bitter edge, whereas hops added later in the process are more aromatic. Just as for malt, there are also many varieties of hops to choose from, and the secret is to find varieties that go well together. We rely on hops from England, Germany, Czech Republic and the United States.

Chilling and monitoring the wort

After about 90 minutes the boil is finished and the wort must be chilled. Cold water flows through a heat-exchanger from which warm water emerges, ready to kick-start the next brew. The important point here is to control the sugar content and temperature. All measurements are carefully monitored and logged in the Brewer’s Daily Log.

First-stage fermentation and harvesting

The chilled wort is pumped into the fermentation tub, a large, open tank with a semi-open lid. This is the key part of the entire Kinn process: open fermentation. Yeast is added from an earlier brew, plus a little additional oxygen. The oxygen helps the yeast multiply to a suitable concentration. About 24 hours later, the first fermentation froth is removed with a spade and discarded. This is the unwanted froth containing undesirable proteins, dead yeast cells and hop residues. After about 3-4 days of fermentation, yeast is harvested for the next brew. Allowing the beer to ferment in open tubs for the first few days is vital for the speciality taste that distinguishes Kinn. Smooth and tender to the tongue, but still a beer with a powerful explosion of flavour.

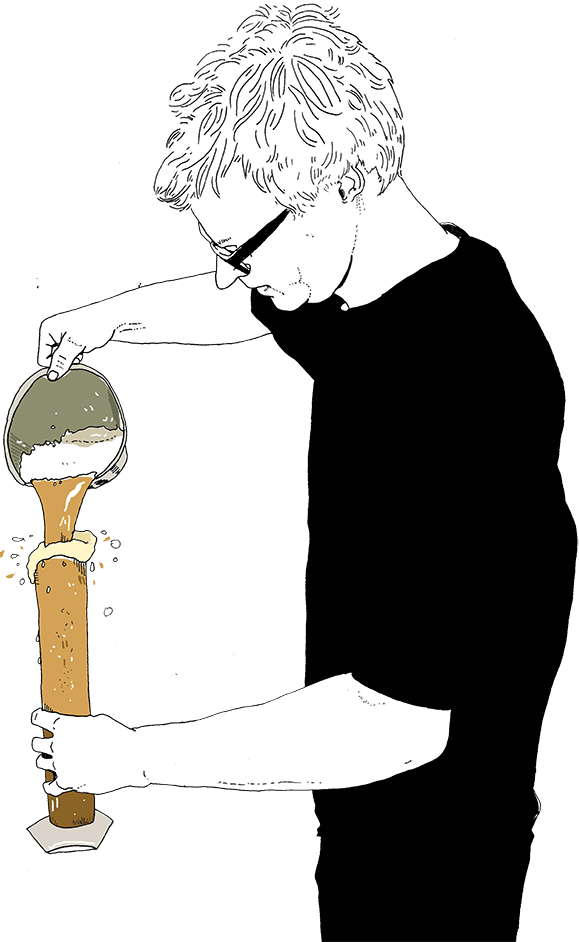

Second-stage beer conditioning

A day or two after the yeast is harvested, almost all fermentation ceases. The test we do is to see if bubbles of carbon dioxide are rising to the surface, giving a dense, compact head on the beer. Now is the time to transfer the beer into a closed conditioning tank where the second stage of fermentation takes place. When stage two is completed, the yeast will start to precipitate on the bottom leaving a clear, transparent brew.

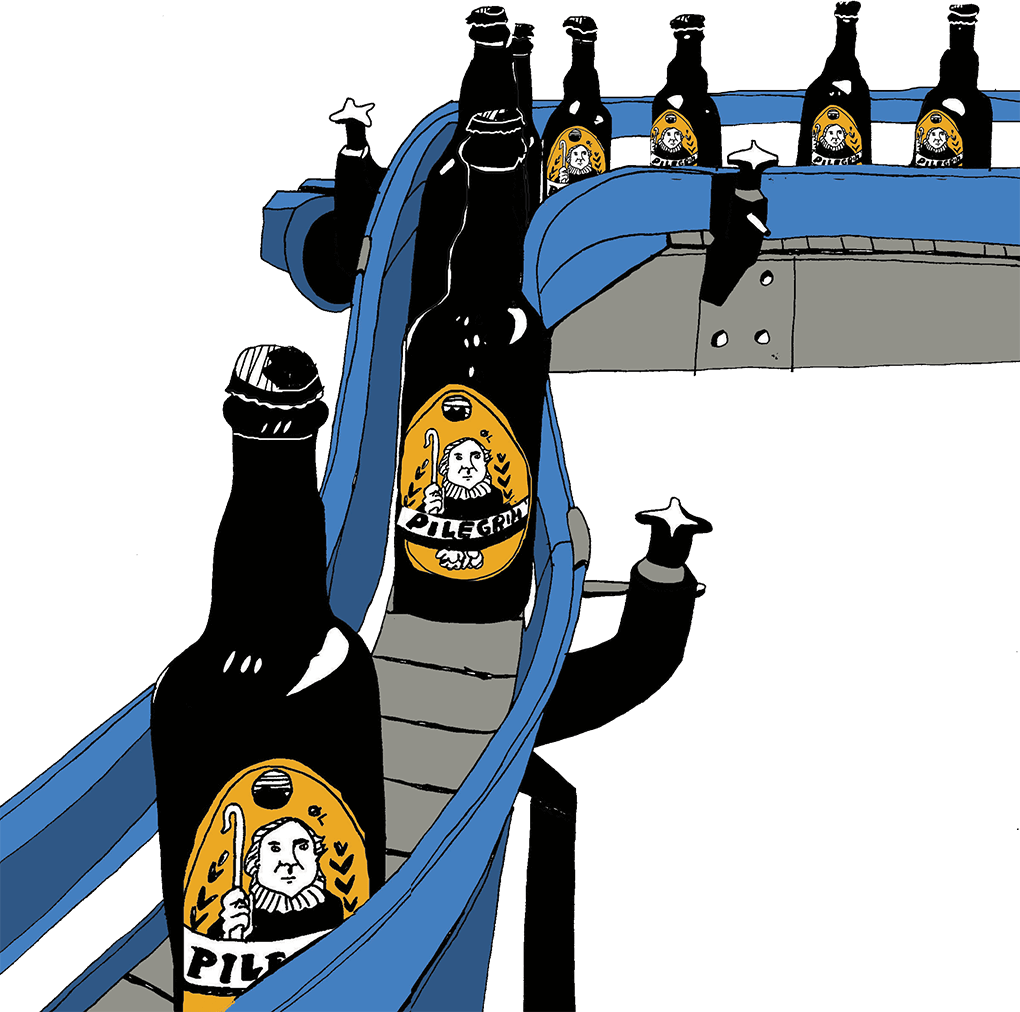

Third-stage carbonation and bottling

After a couple of weeks in the conditioning tank, the clarified beer is ready to enter a pressure-tank with a little added sugar. Since the beer has been neither filtered nor pasteurised, there is still some live yeast in the liquid. The added sugar will energise the yeast for the third-stage fermentation in the bottle or keg, generating carbon dioxide. More sugar means more carbonation gas, which is typical of Belgian beers, whereas less sugar and less carbonation are preferred in English beers.

Our bottling department has some pretty efficient machines, but we still have to keep a watchful eye on the process. After bottling, the beer is kept at room-temperature in a warehouse for a week, where carbonation can proceed at 25 oC.

Finished product

For our milder beers, the process is now completed and the bottles can be shipped to customers. Stronger beers need to mature considerably longer, sometimes as much as two years before hitting the shelves. A special dark and cold cellar is used for the purpose, which keeps the product at around 10-12 oC all year.